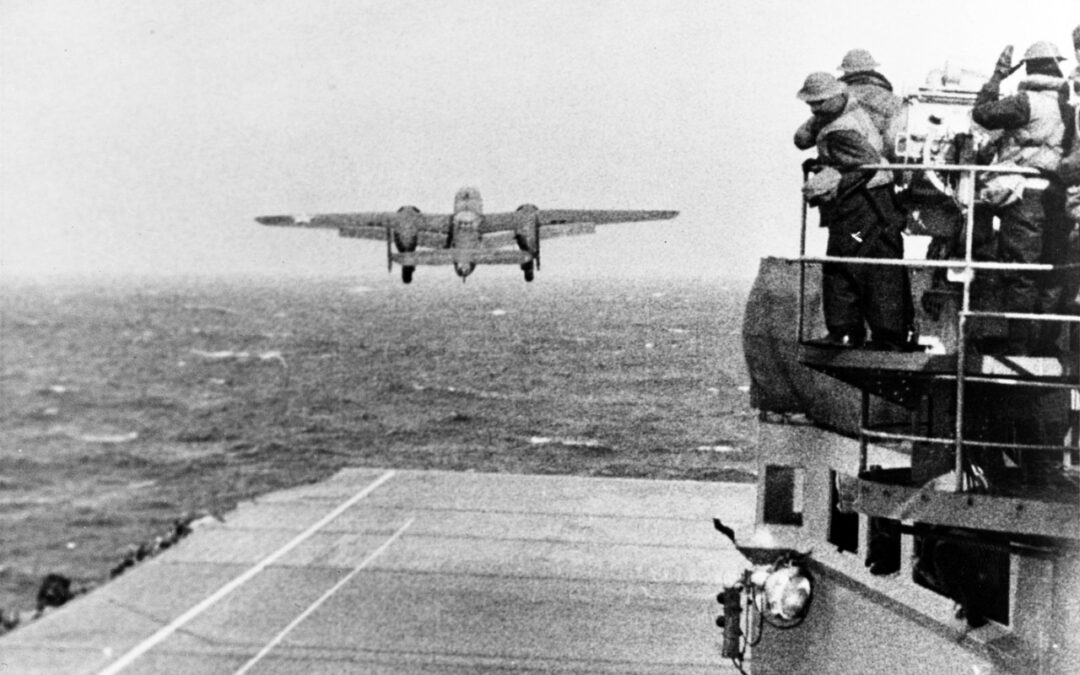

Image: An Army Air Force B-25 Mitchell bomber takes off from USS Hornet (CV-8) at the start of the Doolittle Raid, April 18, 1942.

Article from Naval History and Heritage Command.

Conceived shortly after the deadly Dec. 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor attack that killed more than 2,000 Americans and propelled the United States into World War II, the “joint Army-Navy bombing project” was hatched to inflict “material and psychological” damage against the heart of the Japanese Empire. On April 18, 1942, led by U.S. Army Air Forces Lt. Col. James Doolittle, 16 B-25 Mitchell bombers launched from the aircraft carrier Hornet (CV-8) approximately 650 miles off Japan. Their mission was to attack the Japanese homeland and incite a “fear complex” on the Japanese people. After a longer than anticipated flight, Doolittle’s Raiders dropped high explosive and incendiary bombs on targets in Tokyo, Yokosuka, Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagoya. Originally, the plan was to launch and recover the aircraft much closer to Japan, but the task force was discovered earlier than expected by a Japanese picket boat. The early launch meant that the pilots, after making the bomb run, would have to land in occupied China and hope they wouldn’t be taken prisoner by the Japanese. Of the 16 B-25’s, 15 crashed in China and one landed intact at Vladivostok, where the Soviets interned it and its crew. Two of the crews were captured by Japanese forces after they bailed out, one near the Chinese coast and one near Lake Poyang. The Chinese attempted to purchase the freedom of the captured air crews, but they were unsuccessful. Four of the raiders remained prisoners of the Japanese until the end of the war. One, Lt. Robert J. Meder, died of dysentery in 1943. Three—Lt. Dean Hallmark, Lt. William Farrow, and Sgt. Harold Spatz—were executed by the Japanese in October 1942. Doolittle survived and later was promoted to brigadier general and awarded the Medal of Honor.

Although the attack did little material damage to Japan, the effect of the air raid on the Japanese capital itself was enormous. Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku’s fear of a U.S. carrier strike against the homeland, deemed “unreasonable” by the Naval General Staff, had occurred unimpeded. The Doolittle Raid dissolved the residual doubts harbored within the Japanese staff whether or not a thrust against the important U.S. advanced naval base at Midway, an important element in Yamamoto’s plan to draw out U.S. aircraft carriers, should be attempted. The reality of U.S. bombers over Tokyo skies forced them to accelerate the expansion of their strategic defensive perimeter. This would culminate in the planned invasion of the Midway Islands in the central Pacific. U.S. cryptanalysts had penetrated the Japanese JN25 naval code, however, and Pacific Fleet commander Adm. Chester Nimitz ordered his carriers to intercept the Japanese naval force. At the subsequent Battle of Midway (June 4 – 7, 1942), U.S. naval air power destroyed Japan’s first-line carrier strength and reversed the tide of the war in the Pacific.

After America’s resounding victory at Midway and with the Japanese navy reeling, the Japanese army carried out a terrifying campaign of reprisals against the Chinese. The second Sino-Japanese War had somewhat reached a stalemate in 1942, but the raid highlighted the threat posed by Nationalist-controlled territory along the Chinese coast. Within days of the raid, Japanese planners began formulating a campaign to neutralize the airfields and punish those who were deemed helpful to the Doolittle Raiders. In early June 1942, the Japanese launched an offensive into Chekiang and Kiangsi, and the brutality directed at the civilian population was unspeakable. Trinkets and souvenirs left by the Doolittle Raiders—parachutes, cigarettes, and other military gear—doomed entire villages, as the Japanese judged all the residents as being complicit. Japanese bombers devastated Chuchow and Kiangsi’s provincial capital of Nancheng. Entire populations were simply wiped out. It is estimated that some 250,000 civilians were killed during the reprisal campaign.

As for the raiders, Doolittle, in addition to the nation’s top honor, also received two Distinguished Service Medals, the Silver Star, three Distinguished Flying Crosses, Bronze Star, four Air Medals, and decorations from Great Britain, France, Belgium, Poland, China, and Ecuador for his service during the war. He retired from active service with the Air Force in 1946 as a lieutenant general. He passed away in 1993 at the age of 96 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Lt. Col. Dick Cole, who served as Doolittle’s co-pilot, died in April 2019. He was the last living Doolittle Raider. In 2018, a museum commemorating the raid and celebrating the Chinese villagers who helped the American air crews opened in Chuchow (Quzhou).