Article by the Naval History and Heritage Command.

Carrier pigeons played a role in Naval communications from the late 1880s through World War II.

The Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, was the first command in the Navy to breed and train carrier pigeons. A Naval Academy French professor, Henri Marion, built an experimental pigeon loft in an academy boathouse in 1891. He received the pigeons from the Army’s Signal Corps, which had built an experimental pigeon loft in Key West, Florida, in 1888, but closed their program three years later. While with the Army, the birds had proven their ability to fly over water, routinely carrying messages from Havana, Cuba, back to their loft in Key West.

Convinced that pigeons could improve naval communications at sea, Marion began training the birds on the Naval Academy school ship, USS Constellation. Academy pigeons were conditioned to fly from the ship back to their home loft at Annapolis. They were released from shorter distances at first, then the distance was gradually increased until they were to flying up to 150 miles.

In 1893, the pigeons on Constellation proved their worth in an emergency. A seaman was killed in an accident when Constellation was 12 miles out from Annapolis. Two birds carried duplicate messages requesting that the academy’s screw tug Standish be sent to pick up the body. The message was sent at 0930 on 7 June 1893. Less than three hours later, the Standish was alongside the Constellation.

In 1896, the Navy officially established the U.S. Naval Pigeon Messenger Service. The Secretary of the Navy directed that pigeon lofts be built at Boston Navy Yard, Portsmouth Navy Yard, Naval Station Newport, Brooklyn Navy Yard, Key West, and Mare Island Navy Yard.

When the United States declared war on Spain in April 1898, the Navy’s messenger service birds carried official messages from ship to shore—mostly from ships operating off the East Coast on their way to the Caribbean. The pigeons flew to stationary pigeon lofts along the Atlantic seaboard, carrying messages from the fleet in a small aluminum capsule attached to their leg.

In 1899, the Navy shifted its focus to radio communications. By 1902, all new Navy ships were outfitted with wireless telegraph equipment. With this new technology available, the Navy disestablished the Naval Pigeon Messenger Service and auctioned off all its pigeons.

World War I: Pigeons Return to Service

The U.S. Navy began using homing pigeons again during World War I. Most of the pigeons used on these missions came from military or private lofts in Belgium and France.

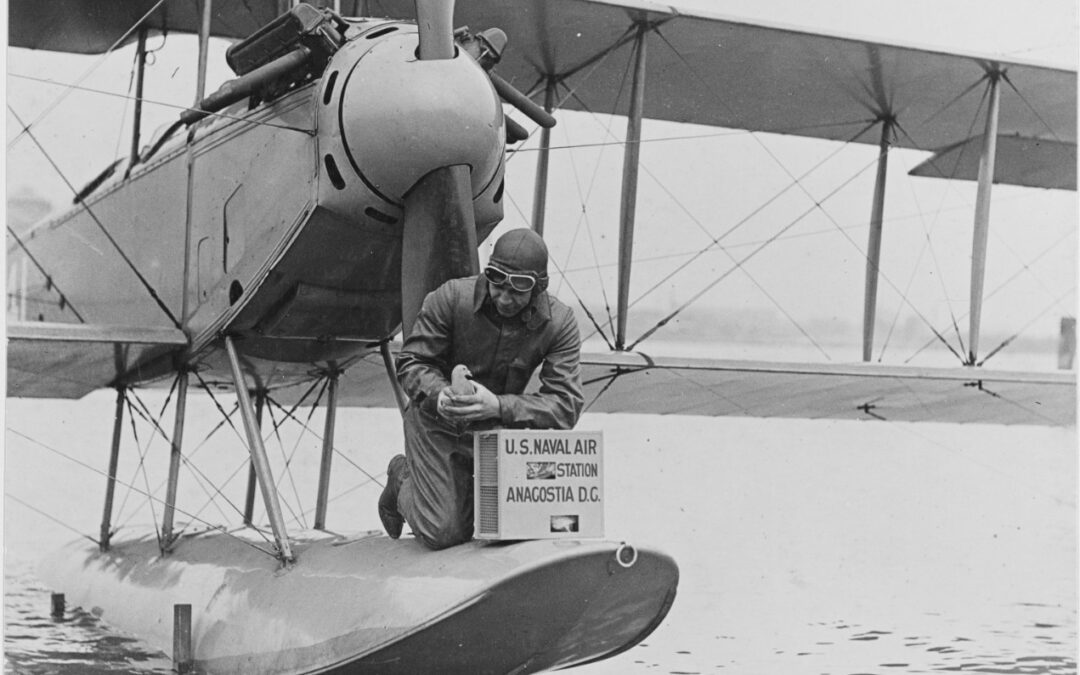

Naval aviators carried them aboard seaplanes while conducting anti-submarine missions along the French coast. The aviators used pigeons to dispatch messages in the event of a crash or other emergency as wireless radio sets were large and cumbersome to carry aboard aircraft. Upon release, the pigeon would carry the message to its home loft at one of the U.S. Navy air stations in France. Once at the pigeon loft, the pigeon would go through a little slot that rang a bell and the pigeon master would retrieve the note.

One notable incident occurred on 22 November 1917, when U.S. Navy Ensign Kenneth R. Smith and his crew departed the U.S. Naval Air Station at Le Croisic, France, in foggy weather and crashed. The pigeons on board were released to deliver an emergency message back to base. A search team subsequently rescued Smith and the crew.

During World War I, the Navy developed a “pigeon trainer” enlisted rate. Pigeoneers, as they were often called, fell under the quartermaster rating. They were identified as Quartermaster (Pigeon), QM(P). Sailors went to a specialist’s school for six to 12 months then received orders to naval air stations with pigeon lofts.

In 1918, the Navy published a manual for pigeon trainers entitled Instructions on Reception, Care and Training of Homing Pigeons in Newly Installed Lofts at U.S. Navy Air Bases. The manual contained detailed information on how the birds should be fed, housed, and trained. It included such things as when to bathe them (every other day and never on extremely cold days); how to build rapport with a bird how to properly hold a bird; how often to clean their perches and nest boxes; and what they should be fed (50 percent Canada peas, 25 percent Argentine corn, 15 percent Kaffir corn or milo maize, and 10 percent whole rice).

Pigeoneers were also required to conduct a daily and monthly inventory of the birds, which included recording the number of breeding pigeons in the loft, the number of trained and untrained birds in the loft, the number of birds “out for immediate duty,” and the number of sick birds in the hospital.

Naval Air Station Anacostia, which ran the largest pigeon school in the country, maintained a loft with 300 birds. They were well cared for, with bright and airy lofts that had running water, electricity, and a hospital ready to provide medical care if they fell ill. Armed guards patrolled their grounds at night.